Unpacking the Foundation of Knowledge

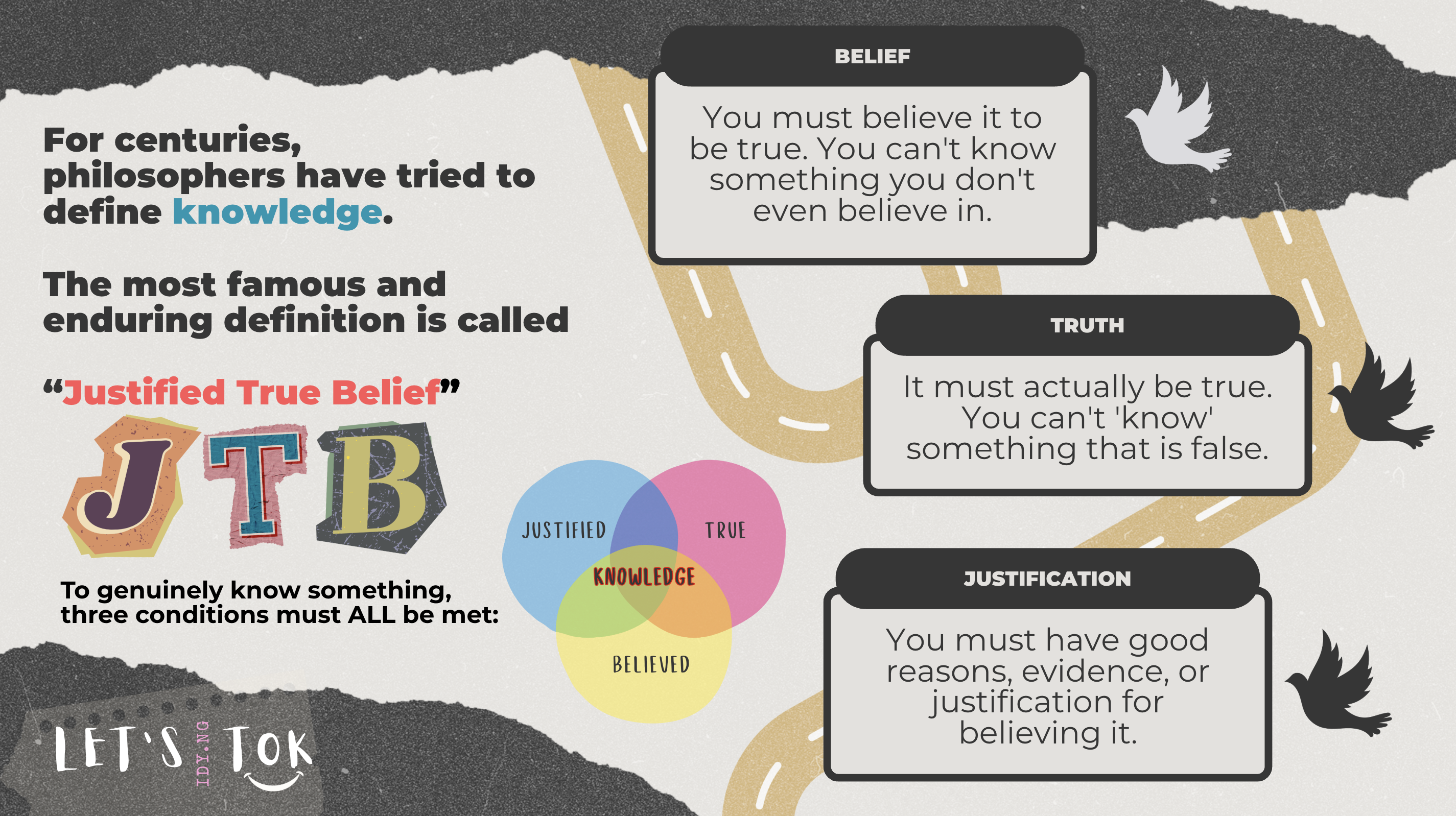

What does it mean to know something? Is it a feeling? A fact you read online? Is it the unwavering confidence of a four-year-old who believes he’s a grandmaster of Rock-Paper-Scissors? This question is at the very heart of Theory of Knowledge (TOK). For over two millennia, the most influential answer has been a simple yet powerful model known as Justified True Belief (JTB).

The Three Pillars of Knowledge: JTB Explained

The JTB model claims that knowledge is not just a guess or an opinion. For a belief to qualify as knowledge, it must satisfy three strict conditions:

- Belief: You must accept that the proposition is true.

- Truth: The proposition must actually be true.

- Justification: You must have good reasons, evidence, or a reliable process for holding your belief.

I saw this play out with my older son, Sam. When he was four, he and his grandma developed a beloved ritual: playing Rock-Paper-Scissors. With the fierce concentration of a chess master, Sam would throw his hand up and declare, “I win! I’m the champion!” His face would beam with the pride of a “big boy” who had skillfully mastered a complex game. He believed he won. And he was true — his paper was indeed covering grandma’s rock. His justification? He saw the result with his own eyes and felt the thrill of victory. By the JTB model, Sam knew he had won.

Why is JTB So Important for TOK?

TOK is not about what we know, but about how we know it. The JTB model provides the essential toolkit for this investigation.

- It Forces Critical Questions: JTB pushes us to ask: “How do I justify this?” Sam’s justification was sense perception—he saw the win. But TOK pushes us to probe deeper. Was his perception of the outcome the same as understanding the process?

- It Evaluates Methods: By focusing on justification, JTB allows us to compare the strength of knowledge. Was Sam’s perception a reliable method for claiming skill, or was it merely recording a result?

- It Builds Intellectual Humility: Understanding that knowledge requires robust justification makes us more discerning. It makes us look beyond the obvious, happy outcome.

The Cracks in the Foundation: Is JTB Enough?

Despite its elegance, philosophers have discovered a critical flaw. In 1963, Edmund Gettier showed that you can have a justified true belief by pure luck, which doesn’t feel like real knowledge.

The Grandma Gambit: A Deeper Look

Let’s analyze Sam’s game through a TOK lens.

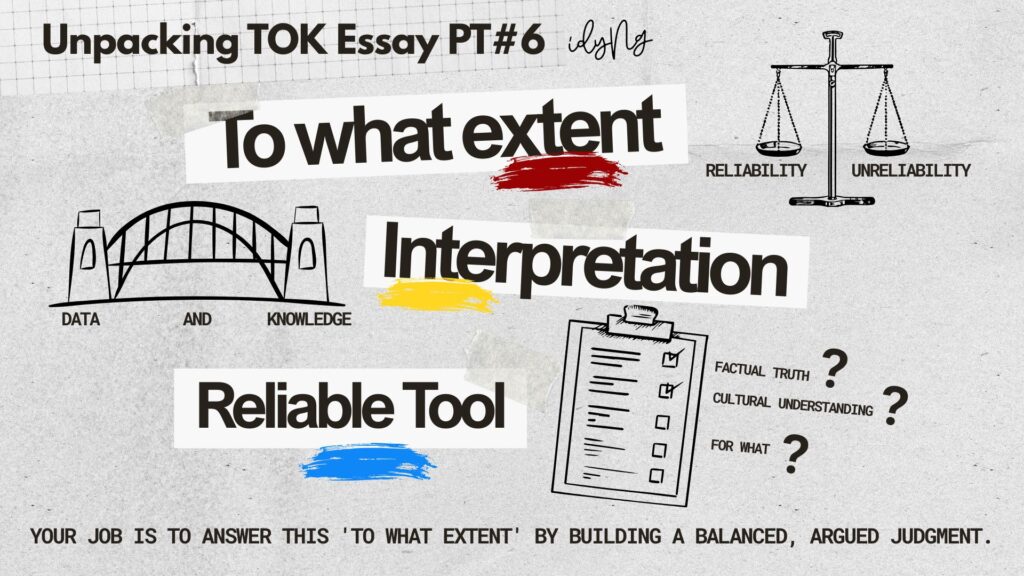

- 4 yr-old Sam’s Knowledge Claim: “I am skilled at Rock-Paper-Scissors and I win because I am good at it.” (A claim about his own ability)

- A Key Knowledge Question: “To what extent is personal experience a reliable justification for claiming skill?”

Sam had a belief in his skill. It was true that he won. His justification was his personal experience of winning and seeing the results.

But his justification was built on a hidden error. His grandma, wanting to see her grandson’s joyful confidence flourish, would see his choice a split-second early and deliberately choose the losing hand. Sam’s justification was flawed. He thought he won by chance and skill, but he consistently won by grandmotherly love. His true belief about his skill was accidental. Did he really know he was a skilled player? We intuitively sense the answer is no. This is a classic “Gettier case” in a heartwarming form, revealing that JTB, while necessary, is not always sufficient for knowledge.

Thinking Further: Your TOK Journey

This charming childhood memory is a perfect microcosm for the problems of knowledge. It shows how our knowledge can be built on unseen assumptions and kind deceptions.

- What makes justification reliable? Sam’s perception was reliable for confirming the outcome (win/lose) but completely unreliable for understanding the cause (skill/love). How often are we confident in our justifications without seeing the whole picture?

- How do emotions and values shape knowledge? Grandma’s love created the entire condition for Sam’s knowledge claim. His confidence was a gift from her values. This pushes us to ask: “How do our emotions and the emotions of others influence what we claim to know?”

- Is there a difference between knowledge and happy ignorance? Sam’s false knowledge brought him genuine happiness and confidence. This raises a profound ethical question: When is it better not to know?

The JTB model is the starting line. It gives you the framework to begin questioning everything. So, the next time you say “I know,” pause and ask yourself: Is this a justified true belief, or do I just have a generous grandma? Your search for a better answer is what TOK is all about.