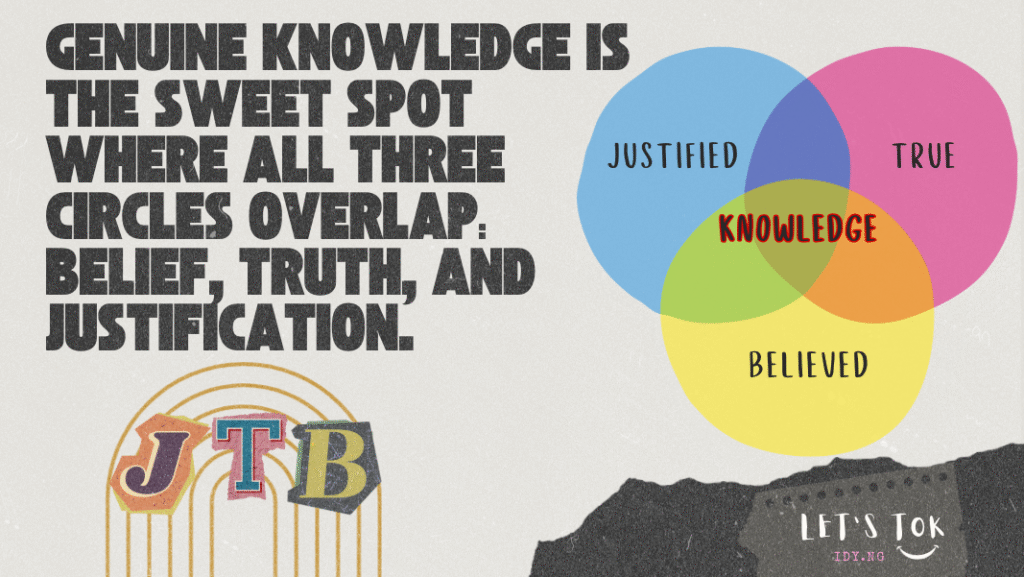

The Justified True Belief theory is a classic definition of knowledge. It states that for someone to truly know a proposition (a statement of fact), three conditions must be met simultaneously:

- Belief: You must believe the statement to be true. You can’t know something you don’t believe in.

- Example: You can’t “know” that the sky is green while simultaneously believing it’s blue.

- Truth: The statement must actually be true. You cannot “know” something that is false. Beliefs can be false, but knowledge cannot.

- Example: If you believe a fake news story, you might believe it, but you don’t know it because it’s not true.

- Justification: You must have good reasons, evidence, or a reliable process for your true belief. It can’t just be a lucky guess.

- Example: You guess that a coin flip will land on heads, and it does. You believed it would be heads, and it was true, but you had no good reason (justification). It was a lucky guess, not knowledge.

In simple terms: Knowledge = Belief + Truth + Justification

Where Did It Come From? A Brief History

The JTB definition of knowledge isn’t the invention of a single person but a concept that evolved over millennia.

- Ancient Roots (Plato):

- The idea is most famously traced back to the ancient Greek philosopher Plato (c. 427–347 BCE), specifically in his dialogue called the “Theaetetus.” In it, Socrates and Theaetetus explore the definition of knowledge and ultimately settle on “true judgment with an account” (a logos), which is the ancient precursor to “justified true belief.” While Plato/Socrates raised some doubts about it, this formulation became the standard starting point for all future discussions.

- The 20th Century Standard:

- For much of modern philosophy, JTB was accepted as the default, common-sense definition of knowledge. It was a useful tool for epistemologists (philosophers who study knowledge) to analyze what we claim to know.

- The Devastating Counterargument (Gettier):

- In 1963, a philosopher named Edmund Gettier published a devastatingly short paper (just three pages) titled “Is Justified True Belief Knowledge?” In it, he provided clever counterexamples (now called “Gettier cases”) that showed how someone could have a justified true belief that still feels like a lucky guess rather than genuine knowledge.

- A classic Gettier Case (Broken clock example):

- Imagine you look at a clock on the wall that says 10:00 AM. You form the belief, “It is 10:00 AM.” Unbeknownst to you, the clock is broken and has been stuck at 10:00 for days.

- However, by sheer coincidence, it actually is 10:00 AM when you look at it.

- Belief? Yes, you believe it’s 10:00 AM.

- Truth? Yes, it is actually 10:00 AM.

- Justification? Yes, you looked at a clock, which is a generally reliable source.

According to JTB, you should know it’s 10:00 AM. But intuitively, it seems you got lucky. Your justification was based on a faulty clock. This seems more like a true belief by accident than real knowledge.

Gettier’s paper shattered the JTB model and launched a whole new era in epistemology, where philosophers have been trying to fix or replace the definition of knowledge ever since (e.g., with “no false premises” or “reliabilism” theories).

How Can You Apply This?

While it may seem abstract, the framework of Justified True Belief is incredibly practical in everyday life, especially in our modern age of information overload.

1. Critical Thinking and Media Literacy

This is the most direct application. When you encounter a claim (especially online), you can use the JTB framework to vet it.

- Belief: Do I find myself believing this? (Be aware of your own biases.)

- Truth: Is this actually true? Can it be verified by multiple independent, reputable sources? Or is it from a single, questionable origin?

- Justification: Why do I believe this? What is my evidence? Is my justification based on reliable data, logical reasoning, and expert consensus, or is it based on emotion, an echo chamber, or a gut feeling?

Example: A headline says, “New Study Proves Chocolate Cures Cancer!”

- JTB Analysis: You might believe it because you want it to be true. But you must check for truth (is the study real? Was it misrepresented?). Then check the justification (was it a robust, peer-reviewed study on humans, or a preliminary test on cells in a lab?).

2. Professional and Academic Work

In any field, from science to law to business, your arguments and conclusions must be built on knowledge, not just opinion.

- Writing a Report: You can’t just state a conclusion (belief). You must ensure it’s accurate (truth) and back it up with data, citations, and sound analysis (justification).

- Making a Business Decision: Proposing a new strategy isn’t enough. You need to justify it with market research, financial projections, and case studies (justification) and have a reasonable belief that it will lead to a positive outcome (truth).

3. Personal Relationships and Disagreements

Often, arguments stem from conflicting beliefs where neither side has examined their own justification.

- Self-Reflection: “I believe my friend was rude to me. Is that true? What was their actual behavior (truth)? What is my justification for interpreting it as rudeness? Could there be another explanation (e.g., they were having a bad day)?”

- Engaging with Others: Instead of just asserting “You’re wrong!” you can ask, “What is your justification for that belief?” This moves the conversation from a clash of beliefs to a discussion of evidence and reasoning.

4. Understanding the Limits of Your Own Knowledge

The JTB model, especially with Gettier’s caveat, teaches us humility. It reminds us that even when we feel very justified in a true belief, we might be right for the wrong reasons. This encourages:

- Intellectual Curiosity: Always being open to new evidence that might challenge your justification.

- Healthy Skepticism: Questioning the sources and strength of your own beliefs, not just others’.

Can this be A Parenting Tool? How Can Parents Apply This?

This isn’t just for philosophers in ivory towers. You use this every day, especially as a parent teaching your child about the world. To make this truly come to life, I’d use my younger son, Guddy, a curious 3-year-old, and our daily life situations as examples.

1. Critical Thinking & The “Why” Phase

Guddy is at the age where he asks “why?” a hundred times a day. The JTB model is your best friend here.

- The Scenario: Guddy points to a furry animal in the park and says, “I know that’s a dog!”

- Your JTB Analysis:

- Belief? Check. He definitely believes it.

- Truth? Is it actually a dog? Upon closer look, you see it’s actually a very large, very fluffy cat. So, it’s not true. Therefore, he believed it, but he didn’t know it. This is a chance to teach him the difference between “I think” and “I know.”

- Justification? If it had been a dog, what was his reason? “Because it has four legs and fur.” You can then talk about how that justification isn’t enough, because cats also have four legs and fur. Real knowledge would need better justification, like hearing it bark or seeing its owner with a leash.

2. Building Trust & Honesty

This framework is great for talking about truth and lies.

- The Scenario: There’s a crashed toy car and a guilty-looking Guddy. You ask what happened and he says, “I don’t know, it just fell!”

- Your JTB Analysis: You might believe he did it ( Belief). It might even be true that he did it (Truth). But what’s your justification? Did you see him do it? Or are you just assuming because he’s nearby? Applying JTB forces you to seek proper justification before concluding you know he’s lying. It prevents false accusations and teaches him the importance of evidence.

3. The “Gettier Problem” in Real Life (The Lucky Guess)

Remember the broken clock 10:00 AM example? This happens with Guddy all the time.

- The Scenario: You’re baking cookies. Guddy, wanting to be helpful, looks at the oven timer —which is broken and always says “5:00″— and proudly announces, “I know the cookies are done!”

- Your JTB Analysis:

- Belief? Yes, he believes they are done.

- Truth? You pull them out, and by sheer luck, they are perfectly done! So, it’s true.

- Justification? His reason was the broken timer, which is a terrible justification. He got lucky.

This is a Gettier Case! He had a justified true belief, but it wasn’t real knowledge. It’s a perfect, funny moment to explain to him why we use a working timer (a reliable justification) and not just a lucky guess.

4. Teaching Him to Build His Own Knowledge

I teach Guddy (actually I talk to Brother Sam often too) to use JTB himself. When he makes a claim, gently ask:

- “That’s an interesting thought, Guddy! Why do you believe that?” (Asking for his Justification)

- “How could we check if that’s true?” (Teaching him to verify Truth)

- “So, now that we’ve looked it up in a book/asked an expert, can you say you know it?” (Helping him form a proper Belief based on knowledge).

By using Guddy in these examples, I turn abstract philosophy into practical parenting tools. It becomes a framework for teaching the brothers about evidence, truth, and the difference between guessing and knowing—skills that will be invaluable for their entire life.

It’s not just about what they know; it’s about how they know it.

Idy NG